The Flying Doctor - Chapter Four

Take one!

The scene called for some innocent love-play in the waters of the Coopers Creek billabong. Flying Doctor Tom Callaghan (Andrew McFarlane) was having a mild fling with Dr Chris Randall (Liz Burch). As they drifted closer, gazing deeply into each other's eyes, the camera zoomed in for the clinch. It was a beautiful, tender moment. Then Liz shrieked:

‘Stop that Andrew!' She slapped his face and started thrashing around in the water.

McFarlane stared. The film crew stared. This wasn't in the script.

‘Stop what?' demanded Australia's leading television heart-throb.

‘Pinching my bottom – Ow! There! You did it again!' Her voice faltered. McFarlane was a long, rangy bloke, but he'd have needed rubber arms to reach her from that distance. ‘If it's not you …' her voice trailed off.

‘Ooh!' yelled Andrew. ‘Something's biting me!'

On the bank, the director was too dumbfounded to yell ‘Cut!' in traditional style as everyone stared at the two love-birds floundering and bawling at each other in the billabong. Then Liz bore aloft a small, green-brown creature.

‘Yabbies!' screamed Liz. ‘They're eating me alive!'

Screaming and choking alternately, she struck out for the shore, closely followed by her pop-eyed Flying Doctor hero, while the crew fell about laughing. Yabbies, the small freshwater crayfish which inhabit Australia's inland lakes and dams, had brought down the Flying Doctors' romantic scene with a splash!

‘Not only were we being eaten alive, the water was absolutely freezing,' Andrew recalled later. ‘Liz hates being cold. She loathes it so much it makes her feel really crabby. Perhaps yabbie would be a better word. They actually have it all on film but had to cut most of it because of the language. I saw an out-take of the stuff that didn't go to air and it was very, very funny.'

Gentle romance had become high comedy.

Take two!

Deborah Kerr was whispering. As Andrew McFarlane approached the great English actress on the stage of Melbourne's Comedy Club, he could barely hear a word she was saying. Neither could the audience. He had no choice but to whisper back. Then the method behind Deborah Kerr's madness became apparent. Two people in the front row had been talking loudly. As Deborah's voice lowered, so did theirs. Soon they were silent, craning forward to catch the words on stage. Deborah stared straight at them and suddenly raised her voice to full, theatrical gusto. The guilty parties bounced back in their seats and remained silent for the rest of the performance. They'd got the message.

It was one of the many tricks of the trade Andrew learnt from the famous star of stage and screen. That role as the fast-talking lawyer in The Day After the Fair raised him to the top bracket of Australian actors. Shortly afterwards he returned to the highly popular The Sullivans and then the ABC television series Patrol Boat and eventually The Flying Doctors. Today, an autographed picture signed, ‘To darling Andrew, all my affection and love always, Deborah Kerr' sits on an oak sideboard in Andrew's dining room to remind him of the day glib comedy became masterful technique.

In many ways these two stories mirror the dual personality of Andrew McFarlane. A classic Gemini (he was born on 6 June 1951) he bears all the characteristics of his star sign as outlined by famous astrologer Marie-Simone. On the one hand he is charming and outgoing and on the other inquisitive, withdrawn and intellectual – his moods as changeable as the weather. Sometimes shy, sometimes outspoken, he shares the twin personality syndrome so common in actors such as world-renowned Gemini's Sir Laurence Olivier, whose formal, withdrawn manner concealed a playful, boyish nature, and Marilyn Monroe, who coquettish charm concealed a deeply troubled individual.

Among Australia's top male leads, McFarlane is regarded as one of the best. He uses an understated style of screen acting. He communicates through facial expressions rather than words. He works assiduously at his trade and takes it very seriously.

‘I do like fully understanding a role, then playing it from deep within. Maybe sometimes I get it so understated it becomes a blur,' said McFarlane, his own toughest critic. ‘You can't hide mistakes. Something happens when you are doing film. The camera is rolling and pointing at you, and it draws something from within. It's like some kind of electrical charge going through you and you really feel yourself being sucked into the lens. There is a saying "That the camera steals your soul". I try to get to the soul of the character I'm playing.'

His perception of Dr Tom Callaghan is complete, but played at the surface.

‘He's a well-rounded character. He makes mistakes. He's impatient and he gets frustrated and he hates being in the outback. He's not that sympathetic to begin with, although I think I could have played him more anti-sympathetic. I probably should have. But basically it's an outback love story with a bit of adventure thrown in. It's good, solid, middle-of-the-road family entertainment.'

Andrew doesn't hate the outback, but he once told critic Andrew Brock he wasn't all that fond of the surrogate outback of the television series.

‘I hate early rising, but we have to get up at 5 a.m. and then stand in the freezing cold and frost in shirt-sleeves and pretend we're having a good time in the outback while some sadist sprays you with water and then turns it to ice with a wind machine.' He sighed. ‘But I suppose everything has a good side. Because we're all maniacs on The Flying Doctors they whip maximum performance from us. On most productions, you get to shoot about four minutes a day of usable footage. We do nine and ten minutes. We've almost got to like it. There's a terrible sado-masochistic element in actors, and unfortunately producers and directors know it … and prey on it!'

Andrew McFarlane's theatrical roots run deep. While on a promotional tour of the USA, he visited relatives in New Hampshire who are very special descendants of Andrew's great uncle – a man he never knew but whose framed sepia photograph has hung on his bedroom wall since he was a child. ‘He is a sort of family legend if you like. I've been hearing stories about him ever since I can remember. He went off to London in the early 1900s, played in Galsworthy plays, then went to Hollywood and was part of the Golden Age. He was a character actor. He did those incredible old movies like The Bride of Frankenstein, The Count of Monte Cristo, Anne of Green Gables and Smilin' Through with Norma Shearer. His name was O.P.Heggie and you see his credits at the end of those old movies they show on late night television. His daughters in America have trunks full of letters from people like George Bernard Shaw.'

The Sullivans, a saga set in World War II, was Andrew's first major role. The Sullivans was also the first Australian drama series – don't dare call it a soapie – which made a favourable impression on overseas viewers.

Andrew played John Sullivan, a do-gooder and a little boring perhaps, but a good chap. ‘He was a bit of a Voltaire,' said Andrew. ‘He was admirable in that sense, but I thought he was a bit of a drip at times, really. I wanted him to have balls, but whenever I said that to the directors and writers, they threw a woman at me. They thought, "Oh he needs to get his rocks off. That'll calm him down." That wasn't what I meant at all.'

After a while, he decided he was tired of John Sullivan, or as he described it: ‘You can only stay in bed with one person for so long. Otherwise you get bored. You've got to get up and have breakfast sometime.'

The producers of The Sullivans thought he was mad. He was leaving a successful show at a time when actors were spending more time in dole queues than in front of the cameras.

‘What are you going to do?' they asked.

‘I don't know,' he said. And he didn't but held firmly to his theory that an actor needed to be out of work to get work. Around this time he made a movie called Break of Day, an interesting project in that most of it was filmed around dawn, giving it a soft, gentle glow. It meant also that even pub scenes were filmed at an hour when the body would rather be doing something sensible, like sleeping. The filming for the pub scene began at 6 a.m. ‘I am meant to be drunk in it so I started drinking white wine at 5 a.m. after getting to bed at 3 am.' Andrew still speaks of it with a feeling akin to horror. ‘By the time we broke for lunch at midday they found me asleep in a drain outside the pub.'

Then along came Patrol Boat, a series based on the small naval ships that patrol Australia's vast and isolated northern coastline looking for drug-runners, bird-smugglers, illegal migrants and foreign invaders. Patrol Boat was also moderately successful overseas.

His character was similar to John Sullivan, another reliable, safe person who never did anything wrong, the sort of image the Royal Australian Navy would like to use in its recruiting campaigns. ‘It's hard to play against type unless you have a very malleable face, but I try and steer myself away and push myself into other areas if I can.'

After Patrol Boat he worked here and there before taking on the role of Dr Tom Callaghan in The Flying Doctors. Dr Tom was a bit of a do-gooder as well, reliable and safe, but Andrew saw potential beyond this characterisation. ‘He's impatient and he gets frustrated and he hates the place. He hates being in the outback. He's not that sympathetic to begin with.'

At the beginning The Flying Doctors was to be no more than a mini-series. Much of it was filmed far from the easily accessible Minyip, out in the dustier parts of New South Wales, out where the legends were born. ‘It wasn't the easiest country to work in because it's hot and it's dry and because of the distances we had to travel. We filmed in a lot of the areas used in the Mad Max movies. It's very stark but it has got its own kind of hypnotic beauty …'

Viewers liked the mini-series. The critics were kind. Crawford Productions and the Nine Network, which screened the mini-series, took the plunge and went into an expensive series. Andrew stayed around for a while but soon the restlessness within him, the dislike of spending too long in one show, overcame the security of a regular pay packet. ‘I need to get some dirt on my face,' he announced. ‘I need some life experience.'

Andrew departed for the culture and excitement of London. Dr Tom departed for the famine and disease of Eritrea.

For a year he lived in London, not working, just absorbing the atmosphere of the city, which he was able to afford to do thanks to a toothpaste commercial. When he returned to Australia he got roles in television series, a telemovie, Barracuda, a feature movie, Boulevard of Broken Dreams, and on the stage.

At the same time Alan Bateman, an experienced producer who had devised, among others, the soapie, Home and Away, had taken over as head of drama for the Nine Network. The ratings for The Flying Doctors had been a little disappointing; Bateman believed all it needed was revamping. Andrew McFarlane and Dr Tom Callaghan could be the answer. He thought how sensible it was sending Dr Tom to Eritrea and not killing him off in a plane crash or with snakebite. Over a pleasant Italian meal, Andrew agreed it would be nice to return. The deal was done. Dr Tom returned to Coopers Crossing. ‘I was away long enough to forget all the lousy location shoots in freezing weather,' said Andrew.

When he walked on to the set again after his absence, one of the hands asked: ‘Is it good to be back?'

‘Yes, it's really nice, actually,' Andrew replied.

‘Oh, it must have been traumatic, though?'

‘What do you mean?' said Andrew, puzzled. ‘Working with all these people again? Having to sign the contract?'

‘No, when you were over there, seeing all that?'

The hand, even though he was working on the set, had become as confused as many viewers had. He thought Andrew had been to Eritrea along with Dr Tom.

The break changed Andrew, as it did his character. ‘Dr Tom is quite different in that he's disillusioned, ‘ Andrew told the Sunday Telegraph. ‘One of the strengths before was that he always saw the other side of things; he was always helping other people. Even when he had problems he knew that he had one and he'd take himself up. He was a good and caring doctor. But this time it's deeper than that. It's not a big fuss. Maybe he'll go back there – he doesn't know – but he just had to get away from it. It was too much to handle … the corruption of it all.'

And Andrew? Had he changed?

‘I've had some really interesting experiences, personal as well as professional, so they change you. You just grow. It's a bit like putting on weight or losing weight. You stay the same person but there are certain changes within you. It's changed me in the sense that when I came back

from England I had a much more positive attitude to my work. I was willing to take a lot more chances in things. I wasn't as inhibited as I used to be … I was prepared to take certain risks and make a fool of myself. The trap with television series is that you can fall back on mannerisms and habits and you're not really progressing, you're consolidating, you're not growing. I think you have to do that as an actor. That's why I put myself out of work at times, too, because I think you're only going to get work and new opportunities if you're out of work.'

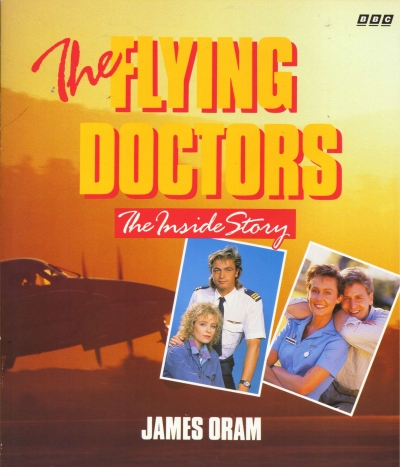

James Oram wrote the book "The Inside Story" about The Flying Doctors and the actors in 1990. Books are only available on eBay or used on Amazon Uk.